Spring cleaning

Hello! So how’s daylight saving time been treating you?

A ways down the front page you may have noticed—nestled between Norman Rockwell and Eddie and the Cruisers—a little six-month gap. New Strategies for Invisibility is hoping not to repeat that phenomenon anytime soon. About it I will say only that I have been working on a couple of non-bloggy projects, about which I hope I’ll have occasion to report more in the months to come. For now, I plan to resume testing your patience with more regularity.

It’s been a little under a year since nice folks at MAKE published the essay of mine that shares its name with this blog; I figure now’s a good a time as any for me to post that essay here. Although the writing that appears in this space doesn’t always resemble it very closely, I’ve often relied on the essay as a kind of blaze while bumbling my way through other stuff. It feels like it belongs here. Thus, interested parties may now locate it by clicking the Thesis tab above.

In other news:

The awesome Greying Ghost Press recently published a limited-edition chapbook (is that redundant?) by my talented and accomplished spouse-person Kathleen Rooney. Titled After Robinson Has Gone, the poems in the chapbook are inspired by the life and work of poet, painter, filmmaker, critic, jazz musician, and all-around midcentury cultural superhero Weldon Kees, who vanished in spectacular fashion in 1955. (In fact, and quite by coincidence, the details of his disappearance are weirdly similar to those of the fictional Eddie Wilson’s in Eddie and the Cruisers.) The chapbooks are individually numbered; each has a unique cover made from an old movie poster. Greying Ghost only made a hundred of these, and considering labor and materials, they’re pretty much giving them away. Pick one up if you can, keep it someplace safe, then flip it after my spouse wins the National Book Award and put your kids through college on the proceeds. Is that some financial planning, or what? I normally charge for that kind of advice.

(Yet more spouse-related goings-on: Kathleen is presently guesting on Harriet, the Poetry Foundation‘s blog, where every month—but particularly April—is National Poetry Month.)

Speaking of the MAKE essay . . . some readers will perhaps recall that it was accompanied in print by an illustration done by my friend Carrie Scanga, who in addition to being a creature of pure goodness is an extraordinarily inventive and skilled visual artist in a variety of forms and materials. Carrie did the cover for K’s first book of poetry, and also for the first book released by Rose Metal Press, and she and her work have been hovering like a benevolent quasi-angelic presence over the creative goings-on in my and K’s household for so long that I’m pleased to now have another occasion to sing her praises. If you are near St. Louis or can get there prior to April 24, please rearrange your affairs in order to visit her show Breathe, which is up at the Craft Alliance Grand Center. Go on my behalf, as it looks unlikely that I’ll be able to make it. Even encountered indirectly—by way of internet traces, and my previous familiarity with her stuff—Breathe looks to be brave and generous and extraordinarily attentive to the fleeting textures of our common embodied lives, and in these senses seems representative of Carrie’s entire project. Your consciousness will be enriched by increased exposure to it.

Other loose ends: in my last post I meant to express a little more affection for the kids at WLUW, the student radio station at Loyola University Chicago, but I couldn’t work it in. Of the two college-radio stations whose signals I drive through on my way home from work—the other one being WNUR—it’s the one I generally enjoy more, if only because its deejays seem sincerely and dorkily enthusiastic about what they’re playing. I love me some dorks.

Speaking of college-radio deejays—whose annealed and rarefied sensibilities keep them constantly at the silk-hankie-slicing katana-edge of underground culture—have y’all seen the video for the latest Ke$ha joint, “Blow?” (That was a joke, son.)

Let’s all just take a moment to process what we’ve just watched. Okay? Okay.

So . . . did you read that thing I wrote awhile back about “TiK ToK?” About how I think it’s, like, basically kind of evil? And how its success may be a symptom of the complete systemic failure of American democracy? That thing?

Yeah, well, I totally stand by that. But, see, here at New Strategies for Invisibility, we get no satisfaction from acting like a bunch of haters. While “TiK ToK” is without question an atrocity that I’d like to see excised like a tumor from our collective cultural brain, I have said all along that Kesha Rose Sebert seems like a basically nice kid with a good head on her shoulders, and I have been sort of sincerely hoping that at some point she’d do something, y’know, good.

I’m not sure if the “Blow” video qualifies, but I will cop to being entirely entertained by it. It seems like everybody involved had a great time making it, which earns a ton of goodwill from me. (One of the things I hated about “TiK ToK” was its lack of genuine playfulness and self-indulgence; this seems to contain healthy quantities of both.) The overall vibe suggests a video project made by bunch of smart, internet-savvy high school seniors with no higher priority than amusing themselves—and who also for some reason have a good production designer and some decent CGI at their disposal. The end result seems rather like a James Bond parody directed by Jean Cocteau, and suggests not only that Ke$ha will be with us for a while yet—which I think by now we’ve all intuited—but that we might not be entirely sorry for this.

Can I make a suggestion? Real quick. Three words: American Idol judge. I’m just saying.

Oh, and I should add: I owe my awareness of the “Blow” video—although what you read here might suggest otherwise, I do not spend a great deal of time monitoring Ke$ha’s activities—to Tim Jones-Yelvington, by way of Facebook. Has everyone been keeping up with Tim’s recent adventures? If you haven’t been, you ought to be; suffice to say that Mary Hamilton’s oft-quoted observation that Tim is “the Lady Gaga of the Chicago lit scene”—while never less than dead-on—has become rather more true since she made it. It’s increasingly easy to imagine Tim’s evolving project as the logical next step in a sequence that runs from Bowie to Madonna to Gaga and beyond. (Where Bowie’s costumes and theater were designed to create slippage between the pop star’s mask and the face behind it, and where Madonna launched a thousand dissertations by embracing that role of pop-star-as-floating-signifier, and Lady Gaga has seemingly READ some of those dissertations and plugged their contents back into her own pop project, Tim is actually using pop forms to DO theory—which is more fun than it sounds like it might be.)

K and I were fortunate enough to be in the audience on November 3, 2010 at the recreation room event at which Tim “came out” as a multiplatform media phenomenon and debuted his Lit Diva Extraordinaire project. In much the same way that literally millions of people claim they were at Woodstock, in much the same way that tens of thousands will tell you they saw the last Sex Pistols show at Winterland, in much the same way that back when I was living in Austin it seemed like every third person in the city swore they were at Liberty Lunch that night in 1994 when Oasis encored with “I Am the Walrus,” and, dude, they knew right then that those guys were gonna be huge, man, huge—people will one day tell such untruths about their presence at that November 3 rec room show. I am not completely kidding about this. And I am telling you right now: K and I were there. And now we are Tim Jones-Yelvingtoning down the Sequined Way. You should join us. Better late than never.

The short answer is: probably this one . . .

. . . but I’m gonna venture to guess that “Dancing in the Dark” is not the song you’re really thinking of.

There is, I suspect, a human tendency—chalk it up to efficiency, I guess—to credit major pop-cultural heroes with greater and more direct influence than they actually possess. The somewhat counterintuitive fact of the matter is that these big names are often just too freaking good to be really useful to the artists who follow them: they’re too accomplished or innovative or sui generis to be productively borrowed from, too successful at their projects to suggest avenues for further exploration.

And this itself, of course, is not an original observation: Harold Bloom argued back in 1973 that the influence of predecessors is something that artists (okay, he was writing specifically about poets, but still) must overcome as much as, or more than, they draw upon it: it’s an obstacle as well as a resource. Bloom catalogues a bunch of approaches and methods by which folks can and have overcome the influence of their major inspirations, a process which he says involves the misprision—or misreading—of significant works. Failure to deliberately misinterpret your predecessors, Bloom says, means your creative output is too faithful and too obviously derivative to contribute much of anything to the ongoing cultural conversation; it will be “weak,” i.e. less than or equal to the sum of its all-too-easily-recognizable parts.

What I don’t love about Bloom’s formulation is its implicit suggestion that the majority of cultural heavy lifting is always done by a handful of heroic figures: that in any particular historical moment it’s always a very small number of artists who move the game forward, and who are themselves always succeeded by another small group that manages to overcome its paralysis by getting its great predecessors’ achievements purposely and compellingly wrong. Meanwhile, Bloom accords the plurality of people producing art at any given time the status of mere spectators, supernumeraries, poseurs, parasites.

I just don’t buy this as an accurate description of how culture actually works. It occurs to me—as it has no doubt occurred to a lot of people—that another way to engage productively with your bigshot predecessors is to rip them off indirectly, specifically by approaching them through the output of their weak imitators: through work that is too obviously derivative to qualify as original, or which attempts a fusion of incompatible elements that doesn’t quite come off (q.v. the infamous woman-fish combo that Horace warns against), or which focuses on great works’ idiosyncrasies and pursues them down self-indulgent dead ends and obsessional culs-de-sac. With all due respect to, like, Beethoven or whomever, mighty oaks do not tend to spring up without some nice rich humified soil to take root in. We need a model of cultural production that accounts for the contributions of the entire ecosystem, right down to the grubs and molds.

Pop music in particular—dependent as it tends to be on collaborative effort and a bunch of constantly-obsolescing technologies—is advanced less by its towering geniuses than by a ton of toiling hobbyists, flameouts, and also-rans who regularly arc across the public consciousness with one really compelling idea and then vanish forever, or who worry a single peculiar notion in obscurity until their motivation finally gutters. Sure, I’m talking about the kinds of phenomena that, for instance, Brian Eno allegedly identified occurring around the first Velvet Underground record (i.e. the almost-nobody-heard-it-but-they-all-started-bands phenomenon)—but I’m also talking about stuff that’s not underappreciated, that doesn’t earn or deserve a cult following, that just shows up and delivers its payload and disappears over the horizon: cheap trash, novelty acts, even some stuff that’s just really, legitimately bad. In popular music, a sweeping vision like Bruce Springsteen’s—which expands and challenges everybody’s sense of what pop can and ought to do—cannot indisputably be assigned a greater value than a single instance of a particular beat perfectly matched to a particular riff:

And if, my young deejay friends, you’ll meditate for a moment on the Romantics’ “What I Like about You,” and you’ll consider (as others certainly have) how its basic rhythmic template might have been used to pump a little adrenal exuberance into the brooding blue-collar streetscapes of Springsteen’s early-80s oeuvre, I think you will arrive at the same conclusion I have—namely, that THIS is the song “Keep the Car Running” is actually reminding us of:

This is about as far removed as you can get from the major heroic figures of the 1980s and still remain inside the confines of what can be called popular music: a one-off hit concealed behind multiple scrims, with origins both circumstantially obscure and deliberately obscured. John Cafferty and the Beaver Brown Band were—let’s count the strikes, shall we?—a Narragansett, RI act with a terrible name and no evident aspirations beyond being unacknowledged understudies to Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band (which at the time was probably not a bad way to earn a living). Here’s the crazy thing, though: when their turn in the national limelight came, it actually required their invisibility. John Cafferty wrote “On the Dark Side” as the signature song of the soon-to-be-cult 1983 film Eddie and the Cruisers, which presented it as the eponymous band’s breakthrough hit: a real song by a fake group. At one point in my suburban-Houston childhood I had in my possession a cassette full of songs I had taped off the radio—you kids are too young to remember this practice; we’d typically do it to pass idle evenings prior to stoking the potbellied stove and turning down the wicks on the gas lamps—and “On the Dark Side” was among these songs. I’d dutifully printed its title on the folded cardstock insert, along with the name of its artist as I’d understood the deejay to give it: Michael Paré. Paré, of course, was the actor who played the Cruisers’ lead singer in the movie. In roughly this manner were John Cafferty and the Beaver Brown Band obscured within, and by, their own solitary hit: a song from a movie that is itself about a singer who scores one big hit and then literally vanishes.

This might be quickly written off as just another instance of Morissettean irony; the actual circumstances are a little more convoluted. When it came out, Eddie and the Cruisers was pretty much a total flop; it slid off screens within three weeks of its September 1983 release date. As its director Martin Davidson recalls (quoted by John Kenneth Muir in The Rock & Roll Film Encyclopedia), he had basically tried to purge the whole sad disaster from his mind when, out of the freaking blue, on the July 4th weekend of the following year, he got a call from some dude at CBS Records. The guy reported that the film’s soundtrack album had suddenly started flying out of CBS’s warehouses: it would eventually come to be certified as triple-platinum by the Recording Industry Association of America. What had happened? Well, evidently Eddie and the Cruisers had entered heavy rotation on cable TV; cable had finally jolted it to cultural life and found it an adoring audience.

At least that’s how the story goes. I’m not completely satisfied by this account either, given what it omits—namely any discussion of the music actually featured on that hit soundtrack. Yeah, no doubt cable TV has turned box-office bombs into cult faves—The Beastmaster, anyone? C’mon, who’s with me?—but I’m not inclined to believe that cable sold three million original soundtrack albums without a little help from other cultural forces, any more than I’m apt to believe that seventeen million people watched and loved The Bodyguard. In the summer of 1984, when folks heard the fictional Eddie singing “On the Dark Side” from their televisions, what exactly were they hearing?

An answer, I think, can be found in another event that occurred at about the same time: Columbia Records released an album called Born in the U.S.A. by an artist named Bruce Springsteen. It hit retailers’ racks on June 4, 1984—exactly a month after the release of “Dancing in the Dark,” the first single from the album, which was then hastening up the charts; it would reach the top spot on Billboard’s Hot Mainstream Rock Tracks within days, and remain there for six weeks. It was, therefore, the number-one rock song in America when Martin Davidson got that call from CBS Records with the news that his movie had risen from the grave, borne aloft by its soundtrack. This is not a coincidence.

According to Muir’s valuable account, when Martin Davidson told his music supervisor to scare up some musicians to serve as the offscreen auditory manifestation of Eddie and the Cruisers, he explained that he was imagining a group that would sound like Dion and the Belmonts by way of the Doors, but that would always remain true to its roots as a New Jersey bar band. It’s tempting, therefore, to summarize Davidson’s vision as Eddie = Dion + the Doors + the Boss, but that’s not quite right. Springsteen had already incorporated Dion & the Belmonts and Jim Morrison into his own sound; he didn’t need Davidson’s made-up movie band to do it for him. (Springsteen has proved no less adept at pastiche than his early-80s Top-40 peers Prince and Madonna, though the Boss’s appropriations have rarely been ironic, and have tended to evoke authenticity more than artifice. In the present context it’s worth noting that his borrowings from the Doors were more successful for being indirect: double-filtered through Iggy Pop and Suicide; cf. “State Trooper” from Nebraska.) It’s more accurate, therefore, to characterize Davidson’s vision as a reduction: Eddie = Springsteen minus Dylan, minus Guthrie, minus Morrison . . . the latter Morrison being Van, not Jim, of course.

Reductiveness has its advantages, as Springsteen himself can testify. In July of 1984 “Dancing in the Dark” had established itself as Springsteen’s biggest chart hit ever; it remains so today. By the accounts of everyone involved, the song was written to be exactly that: during the Born in the U.S.A. sessions, Springsteen’s manager Jon Landau came to him with the news that the album still lacked a lead single; Springsteen did not receive this news with enthusiasm. He banged out “Dancing in the Dark” quickly and spitefully, and that speed and spite come through quite clearly in the finished product. (“Dancing” “went as far in the direction of pop music as I wanted to go,” Springsteen writes in his book Songs, “and probably a little further.” Eric Alterman quotes Steve Van Zant—the E Street Band’s self-designated Cardinal-Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of Straight-Up Rock ’n’ Roll—as pretty much saying that the song only happened because he wasn’t around at the time to kill it.) It remains a bit of an oddball in Springsteen’s output, and not just because it was a huge hit: Max Weinberg’s drums are terse and mechanical, and they, along with Roy Bittan’s plaintive keyboard riff, lend the song what Pandora would call a “synthetic sonority,” something one does not often hear in the Boss’s catalogue, at least not to this extent. The rhythm is pushed rather than swung, closer to disco or New Wave than to the blues; the arrangement seems entirely of its moment, disengaged from cultural and historical precedents.

Although the lyrics seem deeply personal—Bill Flanagan has remarked on how the first line, “I get up in the evening,” is a signal to listeners that Springsteen, the frequent adapter of personae, is here speaking in his own voice (and tweaking and breaking with the blues tradition, too, by shifting “morning” to “evening” in accordance with his own rock-’n’-roll lifestyle)—they also seem pointedly lacking in focus and commitment. Indeed, they are about lacking focus and commitment, as perhaps befits the lyrics of a song Springsteen didn’t really want to write. Right off the bat, the song’s narrator tells us that he “ain’t got nothin’ to say;” he’s just tired and bored with himself, he’s sick of sittin’ ’round here tryin’ to write this hit—er, this book. The placement of “Dancing in the Dark” on Born in the U.S.A.—track eleven of twelve—also reflects some ambivalence on the artist’s part: the song is not the introduction Springsteen wanted to offer guests at his album’s front door, but is rather more akin to a late-night lampshade-on-the-head moment as the festivities are starting to break up.

Needless to say, “Dancing in the Dark” DID serve as an introduction—not to the album, but to Springsteen himself, for millions of folks who’d never heard of him before or who’d never paid that much attention. The song went down easy, and it successfully primed much of the listening public for the material that was to follow. Over half the songs on Born in the U.S.A. eventually hit the Top Ten, and many of these—the tense and brooding “I’m on Fire,” the acerbic and heavily narrative “Glory Days,” the glum and conflicted “My Hometown, “ the indignantly anthemic title track—ain’t exactly bubblegum, hooky though they may be. Still, plenty of the new fans won over by “Dancing in the Dark” did indeed prove willing to go where the Boss wanted to take them.

Plenty of them also didn’t—which is not to say they weren’t willing to go somewhere with him. Much has been made of the ways in which Born in the U.S.A. was misinterpreted and misappropriated by conservatives, and while no doubt some of these misappropriations were opportunistic and dishonest, others were fairly innocent: touching and creepy in approximately equal measure, symptomatic of a peculiarly Reaganite capacity to ignore clear evidence in the interest of a good narrative and to presume concord without any reasonable basis for doing so. George Will, for instance—an incongruously bowtied and earplugged presence at one of the Boss’s marathon concerts in the summer of ’84—saw the huge American flags, saw the disproportionately white and working-class audience, saw the overtly masculine and hetero singer grinning and belting out what sounded like triumphant fight songs, and he must have figured, perhaps not entirely unreasonably, How can this guy NOT be on our team? To Will, Springsteen’s fans looked like exactly the folks who’d crossed historical party lines to land Reagan in the White House, and who were about to vote again to keep him there. And Will—cautious enough to claim Springsteen for conservatism while disavowing any knowledge of the artist’s own politics—was not wrong about those fans.

Through various public statements, Springsteen immediately began to push back against what he regarded as politicians’ and pundits’ misreadings of his songbook—but this could be only so effective given the work itself, which to its credit partakes of an entirely different sort of discourse than does a typical election-season exchange of fire: it’s ambivalent and complex, evoking legacies of pride and disappointment, burdens of social coercion and individual responsibility, and the competing pulls of virtue and duty and impulse and desire, while declining to draw bright lines between any of these. Complex things are by necessity easy to misread; as a result, Springsteen soon found himself contending with the biggest ideological disconnect between a performing artist and a ticket-buying audience this side of Barbra Streisand.

Now, I’d always sort of figured that this ideological disconnect came about due to Born in the U.S.A.’s title track, which is pretty easy to take as prideful and bellicose rather than anguished and aggrieved—particularly if you want to hear it that way, which plenty of people clearly did. It’s worth recalling that in May of 1985, Sylvester Stallone—who hadn’t scored an unambiguous box-office hit doing something other than playing Rocky Balboa since, well, ever—managed to extend his lease on superstardom for another decade essentially by adapting the conservative misreading of “Born in the U.S.A.” to the silver screen. Rambo: First Blood Part II (which had the chutzpah to rewrite not only Springsteen but a half-century of global history AND the movie it’s supposed to be a sequel to) depicts a world where the sufferings of America’s Vietnam combat veterans have been caused not by a lack of decent blue-collar civilian jobs and access to appropriate social services—nor by the, y’know, actual experience of war—but rather by a bunch of mendacious and cowardly bureaucrats. Hell, as a matter of fact (the film seems to suggest) we ought to give our boys another crack at it—this time without all that high-minded best-and-brightest John F. Kennedy claptrap—and by god they’ll get the job done this time. (Pretty much everybody Rambo kills in Vietnam is conspicuously not Vietnamese, i.e. not somebody with an understandable interest in defending home and family from foreign adventurers: Rambo’s major adversaries are all Soviet spetsnaz guys. Suffice to say that the film does not spend a ton of time pondering the validity of the domino theory.) Sadly, there can be no question that misreadings of Born in the U.S.A. helped make Stallone’s blockbuster film possible—misreadings of which in turn helped make the 1991 Gulf War possible, misreadings of which in turn helped make possible the invasions and occupations of Afghanistan and Iraq.

So . . . that’s not too cool. But now that you kids have brought up this whole Arcade Fire issue, it suddenly occurs to me that I have perhaps been too hard on “Born in the U.S.A.” all these years, or at least that I’ve been asking it to shoulder an unfair share of blame for being conscripted by policies it meant to critique. I think what cracked the door to the large-scale misreading of “Born in the U.S.A.” was, in fact, “Dancing in the Dark”—the song that initially seized everybody’s attention, and yet didn’t require anyone to have much of an opinion about it; the song that allowed America to get comfortable with Springsteen and to feel like they pretty much knew where he was coming from. That comfort level actually made it much harder to listen attentively to and to parse the singles that followed it onto the radio. I’m not going to try to argue that “Dancing in the Dark” is a failure—had it never been released, I’m not sure the E Street Band would, for instance, be playing Super Bowl halftime shows—but I DO think it inflicted permanent harm on Springsteen’s overall project in a way that can’t ever really be repaired or undone.

So what’s wrong with “Dancing in the Dark?” Well, nothing: plenty of really great pop singles—probably the majority of them—work pretty much the same way that it does, and I wouldn’t want that to be otherwise. Problems only crop up when the artist who records the pop single doesn’t really want to be regarded as a pop act, which proved to be the case here. Most of Springsteen’s best songs are designed to reward close critical attention: they want you to consider whether the singer is speaking in his own voice or the voice of a character, and, if the latter, what that character’s circumstances might be; as we said earlier, the perspectives they open for the listener on these circumstances tend to be complex and ambivalent. These songs function, in other words, as fictions in the proper sense (i.e. not simply in the sense that they’re “made up”).

“Dancing in the Dark” is a pretty good song, but it’s NOT complex, and it’s not ambivalent; instead it’s calculatedly ambiguous, evoking the specific textures of the narrator’s existence less than the obscure gravitational pull of latent offscreen possibility beckoning from the margins of day-to-day life. “There’s something happening somewhere,” the narrator tells us; this is the same somewhere that haunts an entire American songbook of yearning, from “Over the Rainbow” on down the line. Springsteen uses this kind of thrilling ambiguity all the time—I tear into the guts of something in the night; last night I met this guy and I’m gonna do a little favor for him; there’s a darkness on the edge of town; I guess there’s just a meanness in this world—but he rarely employs it in so pure a form as he does here. “Dancing in the Dark” has depth, sure, but it’s also really simple: it’s brainstem music, no less so than “What I Like About You.” Its topography is less that of verisimilar, mirror-on-the-high-road fiction than the misty nocturnal landscapes of myth; it evokes oceans of human mystery, but the closer you look at it, the less it actually discloses.

My point here, basically, is this: what “Dancing in the Dark” somewhat incautiously succeeded in doing upon its release in the spring of 1984 is conjuring among the record-buying public a vision of a new American pop hero—a cool, brooding exemplar of self-involved masculine subjectivity in the classic mold of Elvis Presley and/or Bob Dylan, Marlon Brando and/or Steve McQueen—whom Bruce Springsteen then gracefully declined to embody, or as least declined to limit himself to embodying. In Springsteen’s mind the song may have been little more than what Dave Hickey might call a term paper, but its directness still evoked an iconic protagonist—a restless, hungry void—who cut a very attractive figure for many listeners. (And this seems about right; at least one novelist would later set out to capture the character of the 1980s through a protagonist who is also a restless, hungry void.) Unfortunately for those listeners, the remainder of Born in the U.S.A. doesn’t include any repeat appearances by this guy; its other songs are by turns too fraught, too specific, too menacing, or too droll, leaving the “Dancing”-smitten audience with nowhere to go for another round of urgent romantic emptiness—nowhere, that is, until they heard John Cafferty’s voice coming out of their TV sets, synched up with Michael Paré’s mouth.

“On the Dark Side” happily delivered on what Born in the U.S.A. withheld—and, perhaps more importantly, it also avoided the kinds of complications that Springsteen’s other songs insisted on delivering. People who wanted to consume “Dancing in the Dark” as a pure pop artifact tended to get distracted by a need to situate it in the context of Springsteen’s entire project and body of work; with “On the Dark Side,” however, that kind of effort was not only unnecessary but impossible: the singer who performed it a) had mysteriously vanished and b) wasn’t a real person anyway. Consequently there was no need to reconcile it with anything. “It seems more real today,” Muir quotes Davidson as saying. “Now if [people] hear ‘On the Dark Side,’ they say, ‘I remember that, that really was number one.’ But it was number one twenty years ago, not forty years ago. The fiction has become a reality.” As Cafferty’s song itself assures us in its opening line, the dark side is calling now nothing is real; if you’re looking for a contemporary lyric that really captures the character of its era—and I’m not just talking about “the Eighties,” but rather a period that begins roughly when the Federal Reserve takes over the national economy in October ’79 and ends in, oh, let’s say September of ’01—you could certainly do worse than this one.

Thus, through their contribution to the Eddie and the Cruisers soundtrack, John Cafferty and the Beaver Brown Band went from being locally-known musicians obscured by their weak faithful reading of Springsteen to nationally-unknown musicians obscured by somebody else’s deliberate misreading of Springsteen. “On the Dark Side” made its way onto the national airwaves as a perfect solution to the Born in the U.S.A. problem: it was a pure hit with no artist, unburdened by any connection to the real world. It may be no better than the sum of its parts (or the difference of its exclusions), but the very modesty of its ambition means that it’s pretty much free of its influences’ baggage; it’s a perfectly portable piece of pop, as straightforward and standardized as a screwdriver, readily available for the use of anyone who needs it.

Although they experienced their suburban-Houston childhood some ten years after I did my own, I feel certain that Win and Will Butler also heard “On the Dark Side” on the radio from time to time while growing up, along with the various hits from Born in the U.S.A. Years later, as they and the other members of Arcade Fire worked on the song that would become “Keep the Car Running,” perhaps they were briefly beset by a moment of anxiety of a type that I have to guess many songwriters encounter after coming up with a great hook: This is awesome, I imagine them thinking, but are we ripping somebody off here? I imagine them listening with care to their own song—sounds a little Springsteeny, huh?—then reviewing mental catalogues of influences, obsessions, and heroes living and dead, and finding, to their probable relief, no matches.

Let me be clear: I’m not looking to call Arcade Fire out for subliminally borrowing from “On the Dark Side.” Neither am I here to argue that the genetic similarity of “Keep the Car Running” to MOR soundtrack fare in any way diminishes what I think is a pretty good song. I just think it’s interesting to consider how Arcade Fire might have been able to use John Cafferty and the Beaver Brown Band—whom I will not refer to as one of Arcade Fire’s influences, any more than I will refer to the sandwich I ate for lunch as one of my internal organs—to engage productively and indirectly with the Boss. If you’re a fan who understands why Springsteen is a great songwriter, as I believe the Arcade Fire kids are, then you’re going to approach him with too much reverence to ransack his songbook and steal what you need. If, on the other hand, you happen upon somebody else’s approximation of Springsteen, then you’re probably going to think: I see what these guys are aiming at, and I see what they’re missing, and I’m pretty sure I could do better than this. In such a manner does the football of art move down the field of cultural production.

Because, hey, let’s take a quick look at what’s going on in “Keep the Car Running.” Its desperate and giddy urgency, its sense of flight from some unnamed or unnamable coercive force, its nocturnal setting and its automotive theme—these all seem very Bruce Springsteen. Not much else about the song does, though: there’s no distinct persona narrating it, and Springsteen’s trademark rooted and gritty specificity is also nowhere in evidence. These are exactly the omissions that defined “Dancing in the Dark”—and exactly the alterations to the basic Springsteen template that yielded “On the Dark Side.” But while “Dancing in the Dark” made these omissions out of impatient, almost accidental candor, and while “On the Dark Side” was essentially a movie prop—a myth made to order, the audio equivalent of an empty façade on a studio backlot—“Keep the Car Running” takes them as a starting point for something more artful and deliberate.

Although it lacks the overtly fictional elements you might find, say, in a song from Nebraska—i.e. characters, setting, backstory, etc.—Arcade Fire still manages to goose “Keep the Car Running” with a surprising degree of plot-level suspense: it’s a car chase in search of an action film. (In this it borrows yet another 1980s pop music device, namely the weird tradition of songs that claim situational drama yet contain little or no actual narrative: though it’s too detailed and specific to be typical, “Life During Wartime” may be the granddaddy here, with its DeLillo-esque evocation of floating-signifier domestic terrorism; “Love Vigilantes” is probably a little too conventionally fictional to qualify. The representative examples are probably goofily portentous MOR hits like “In the Air Tonight” and “Silent Running;” I have no theory to explain why the post-Peter-Gabriel Genesis lineup would be so fond of running this particular play.) “Keep the Car Running” also ducks fiction’s conventional requirements of by announcing itself as a dream song in its first line; this has a bracketing effect functionally similar to the presentation of “On the Dark Side” as a hit by a made-up artist. As the song unmoors itself from references to everyday experience it becomes more stylized, more emotional and abstract, closer to the realm of fable or myth; this rhetoric is reinforced by Arcade Fire’s use of horns, strings, bouzouki, and hurdy-gurdy, folk instruments that are practically prehistoric, never mind pre-rock.

In the realm of pop, myth has a number of uses and misuses. In the best circumstances, it allows artists to sweep aside the complications of verisimilitude to address fundamental things, and also provides a metaphorical language for talking about them. On the whole, Arcade Fire is doing this pretty successfully in “Keep the Car Running.” Sure, there are some unclimbable mountains and unswimmable rivers that do nothing but assert that we’ve entered a realm of quasi-Taoist mystery, as well as a few lines (“same place animals go when they die”) that are evocative but don’t actually evoke much of anything. (This is all still quite a bit less silly than a song that informs us—and that only informs us—that a woman has stepped from the darkness and made the narrator feel crazy and mean, while bringing him to the realization that nothing is real.)

Still, there are some moments in “Keep the Car Running” where Arcade Fire do seem to have their hooks in something significant—not Springsteen’s sought-after “something happening somewhere,” nor quite his sinister “meanness in this world,” but something bad and difficult to apprehend, something bound up with language itself. The city through which the narrator flees frustrates him by changing its name; we get the sense that perhaps, as in a fairy tale, learning its true name might permit him to escape it. Meanwhile, the men who pursue the narrator know his name—he has told it to them—and we get the sense that their power comes from this knowledge, but also that there are limits to this power, and that its balance stands to be reversed. “There’s a fear I keep so deep,” Win Butler sings. “Knew its name since before I could speak.” His and his bandmates’ voices then name that fear; its name is not a word.

The more Arcade Fire I hear, the more it seems like myth is intrinsic to their working methods—which I suppose makes sense, given the Butlers’ own suburban origins and their recent focus on suburban milieus as their subject. In myth, events are ruled by fate rather than by accident; myth’s concept of time is cyclical (every night my dream’s the same / same old city with a different name) rather than sequential (got in a little hometown jam / so they put a rifle in my hand / sent me off to a foreign land / to go and kill the yellow man). Myth, then, is the opposite of history. Suburbs are always designed with the goals of preventing accident and escaping history; ergo suburbs inevitably suggest themselves as mythic landscapes. Arcade Fire seems to have interesting things to say about the suburbs; it remains to be seen whether they can continue to do this inside the mythic language the suburbs gave them.

This is, I hope, something Butler, Butler, Chassagne & Co. will continue to get better at. They can certainly look to Springsteen’s career for hints on how to do it effectively, and also for examples of missteps they might seek to avoid. For a few years now, journalists have been making suggestions that the band is ill-at-ease with its success; I can only imagine that their recent Grammy win might amplify that. The concern, evidently, is that as their audiences have grown, the band’s perceived capacity to really connect with them has shrunk. Arcade Fire, it seems, is anxious about being misread. We can only assume their friend and mentor Bruce Springsteen has assured them that this concern is indeed justified—has warned them how quickly your use of myth can turn into myth’s use of you.

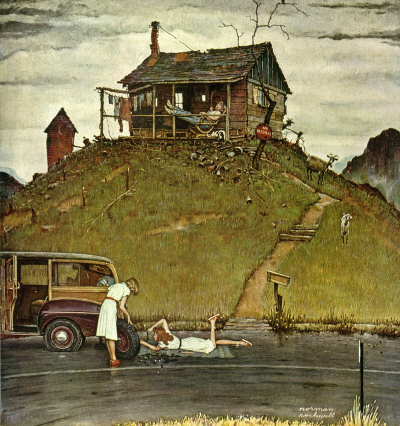

Norman Rockwell: The Movie!

Our next scheduled post—on Gold Diggers of 1933—has been delayed so New Strategies for Invisibility can take a shot at Deborah Solomon.

You saw her feature on Norman Rockwell in the Sunday arts section of the NYT last month, right? The article’s ostensible occasion was the opening of a Rockwell exhibition that’s up now at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the contents of which are drawn from the private collections of filmmakers George Lucas and Stephen Spielberg. The Sunday on which Solomon’s article ran was Independence Day—and if there’s anything more American than Norman Rockwell, it’s the combined luxury-good purchasing power wielded by George Lucas and Stephen Spielberg! God bless the U.S.A.!

Deborah Solomon, as you are no doubt aware, is responsible for the brief, punchy, often confrontational, always entirely implausible “Questions for” feature that runs weekly in the New York Times Magazine. “Questions for” is notable chiefly for its adaptation to print of the subtractive compositional techniques of reality television, i.e. the editing-down of long stretches of unscripted human interaction into episodes of maximal drama and minimal nuance. I have been reading it for years with growing irritation and am now convinced—in keeping with today’s theme, and to quote Jon Stewart out of context—that it is hurting America.

But let’s not talk about “Questions for.” Let’s talk about Norman Rockwell—about whom, the internet informs me, Solomon is presently completing a biography. (We can add to the magic confluence of Rockwell, Spielberg, Lucas, and July 4th the NYT’s apparently inexhaustible willingness to let prominent contributors use their features to drum up interest in their own projects.) It’s hardly crazy for Solomon to be working this beat—she has previously published biographies of Jackson Pollock and Joseph Cornell, and was for many years an art critic for that dynamo of the avant-garde, the Wall Street Journal—so I am willing exercise some charity and deference here with respect to her qualifications.

And honestly, as a piece of newspaper journalism, her piece isn’t a total waste of time. If you ignore Solomon’s lame attempts to suggest inter-filmmaker resentment between Lucas and Spielberg—force of habit, eh, Debz?—she’s pretty perceptive about the values implicit in Rockwell’s work, and its place in the culture.

Oh, but then there’s this:

As beloved as [Rockwell] was by the public, he suffered the slings of critical derision, especially in the ’50s. The dominant art movements of that era—Abstract Expressionism, Beat poetry and hard bop jazz—devalued craftsmanship in favor of improvisation and the raw, unmediated gesture. Against this backdrop Rockwell was accused of purveying an artificial and squeaky-clean view of America, which remains a criticism of him today.

It is true that his work, for the most part, does not acknowledge social hardships or injustice. It does not offer a sustained meditation on heartbreak or death. Yet why should it? Idealization has been a reputable tradition in art at least since the days when the Greeks put up the Parthenon, and Rockwell’s work is no more unrealistic than that of countless art-history legends, like Mondrian, whose geometric compositions exemplify an ideal of harmony and calm, or Watteau, who invented the genre of the fête galante. Rockwell perfected a style of painting that might be called the American Ideal. Instead of taking place in lush European gardens, his playful gatherings are in a diner on Main Street.

This is not so much completely as it is exactly wrong. It is NOT true that Rockwell’s work “does not acknowledge social hardships or injustice.” It just doesn’t depict them as insurmountable—provided we can approach them with sympathy for the perspective of our adversaries, and our adversaries can do the same. This may not be likely, but it is certainly possible, and Rockwell demonstrates this possibility by not only depicting but encouraging it—and creating a rhetorical space in which it can occur—through his popular illustrations.

The suggestion that Rockwell’s work is inferior to the raw and gestural output of his modernist contemporaries is specious, given that he begins and proceeds with completely different assumptions and aims. No, Rockwell doesn’t “offer a sustained meditation on heartbreak or death”—because heartbreak and death are by definition solitary, and sustained meditation on them presupposes a laudatory interest in the subjective experience of the heroic individual. Rockwell has no such interest. His work is comic, in the old Greek sense: it’s concerned with individuals only to extent that communities are made up of them.

A comic sensibility and an “idealistic” worldview are not remotely the same thing. (I’m not even sure they can comfortably coexist in the same consciousness, since comedy depends on instances of gears not meshing.) The first mistake that Solomon makes here—presumably as her editors are tapping their feet and glancing at their watches—is not so much to mischaracterize Rockwell’s work as to misapply her terminology: she’s conflating “idealistic” in its everyday sense (i.e. referring to those among us who won’t accommodate our lofty principles to the experience of actually living in the world) with “idealist” in its philosophical sense (i.e. referring, in epistemology, to the argument that we can never have certain knowledge of the external world but only the contents of our own minds, or, in metaphysics, to the argument that the external world has no absolute existence at all).

I suspect that Solomon realized as she was typing that she’d drifted across the center stripe, and I guess she deserves some semi-respectful tip of the hat for just putting the pedal down and going for it: viz. her unapologetically loopy comparison of Rockwell to Piet Mondrian, an honest-to-god theosophical idealist who sought in his work to distill the visible world into primary colors and right-angled lines. Her reference to Antoine Watteau is more defensible, though still wrong: while Rockwell’s lightness and his stop-motion evocation of fleeting moments do recall Watteau—and there are parallels (probably misleading ones) to be drawn between Rockwell’s emergence as a brand and Watteau’s establishment of the genre of the fête galante—fundamentally they are two very different artists.

Watteau is rarely narrative in the conventional sense. His canvases of frolicking aristocrats and costumed entertainers tend to give us the impression that we’re peeking through a summer haze to glimpse a titillating story-in-progress, but the key to their effectiveness and their appeal is that we can never quite figure out what the hell’s going on. In Rockwell, what’s going on may not be immediately apparent, but we are damn sure meant to figure it out—and the longer we study each of his images, the more detail emerges to add nuance to their implied narratives. Watteau’s paintings invite us into an imaginary world: diffuse and muted, languorous and ephemeral—akin, maybe, to the “floating world” depicted in Japanese prints—and in any event distinct from the quotidian realm in which we all live and strive. Rockwell’s illustrations, on the other hand, locate us imaginatively IN the everyday world. They depend for their effectiveness on the cultural competency of their viewers: our ability and our willingness to catch the artist’s references and to appreciate his implications. For most artists working in a recognized genre—whether we’re talking about directors shooting post-Hitchcock slasher films, or novelists writing post-Tolkien fantasy, or painters producing post-Watteau fêtes galantes—the big advantage of genre is that it allows you (and your audience) to bypass a bunch of issues related to verisimilitude and “realism.” That’s not at all what Rockwell is up to. Contrary to Solomon’s suggestion, Rockwell is not generic but rhetorical: he engages with verisimilitude head-on, advocating, demonstrating, arguing for a particular kind of perceptiveness. If we can look at the world with the same sympathy and suspended judgment that we look at his illustrations, Rockwell seems to suggest, our attention stands to receive the same rewards.

Key to Rockwell’s skill as a narrative illustrator is his ability to portray spaces that are less architectural or theatrical than social: he excels at conveying a sense of people thinking, interacting, regarding each other. This is not something that Watteau does, or seems very much interested in doing. When I think about Rockwell’s canonical influences—worth thinking about, since art-historical allusions crop up regularly in his work—my brain tends to gravitate toward the hyperreal images of the Mannerists, particularly those of Paolo Veronese, whose fondness for depicting startling perspectives of distorted figures in unholdable poses Rockwell seems to share, along with a gift for suggesting complex multi-character narratives in a single frozen instant through expression, attitude, and gaze.

I also think of Rockwell in relation to a distinct lineage of painters that begins with Caravaggio: Frans Hals, Rembrandt, La Tour, Joseph Wright of Derby . . . guys that David Hockney would identify as “optical” painters, i.e. painters who either used optical devices (lenses, curved mirrors, cameras obscura and lucida) to produce their work, or else tried to emulate the effects of such devices.

Hockney’s speculations about these painters’ methods are controversial. I find them pretty persuasive myself, and anyway compelling as hell. About Rockwell’s own use of optics, however, there is no question: he famously based his paintings on carefully-composed photographs that he’d trace onto his canvases with the aid of a Balopticon projector, a process that helps account for their distinctive sharpness. For me, Rockwell’s reliance on photographs strongly recalls some of Hockney’s assertions about Caravaggio, who left behind a bunch of paintings but not a single sketch, who was accused by his contemporaries of being unable to paint without models present, and who has recently been alleged to have used not only optical devices but primitive chemical fixatives to capture projected images on his canvases.

The part of Hockney’s theory that’s most interesting to me (and almost certainly to him too) is not its “gotcha” aspect, i.e. the issue of which Old Masters used optics and which didn’t—a gossipy debate that has flickered intermittently over the past decade through the pages of various haute-bourgeois magazines in a kind of leisure-class parallel to the pro-sports doping scandals. Rather, it’s the account his theory offers of how a particular style of 2D representation came not only to dominate the Western pictorial tradition but also to be universally and uncritically accepted as the most accurate kind of 2D representation available to us. Hockney points out that we don’t remotely see the moving, blurry, peripherally-glimpsed, selectively-focused-upon world around us in the same way that a camera lens does; in a famous 1984 interview with the New Yorker he derisively characterized photography as “looking at the world from the point of view of a paralyzed cyclops—for a split second.”

I don’t really want to unpack Hockney’s entire argument here. I will say that it’s worthwhile in a general sense to think about what kinds of visual experience photographs are good and not so good at capturing, and also about how photos—and images that resemble them—go about convincing us of their integrity, veracity, and authority. More specifically, and in the present context, it’s interesting to ask: why did Norman Rockwell paint the way he did? Why did his illustrations look the way they looked, and why did he use his particular methods to achieve that look? Why was he a painter in the first place, instead of, say, a photographer? Or—not to put too fine a point on it—why didn’t the magazine editors who made him rich just hire themselves a photographer instead?

Partly, sure, there’s the somewhat vulgar but still undeniable appeal of Rockwell’s full-on, holy-cow virtuosity: the dumb satisfaction—known to generations of Yngwie Malmsteen fans—of watching somebody take aim at something and just hit the living crap out of it. On a technical level, dude was just a scary good painter. (And as Hockney is always at pains to point out, the camera is not a shortcut for the painters who use it; it just introduces a whole new batch of technical challenges.) But virtuosity is not Rockwell’s whole appeal, nor even the bulk of it. When we call something “Rockwellesque,” we don’t mean that it’s extremely sharply rendered, or adroitly executed. We mean something else.

To make an obvious but still important point, the difference between a photograph and a representational painting is that the painting contains no accidents. Because every mark has been made laboriously by the painter, each must be assumed to be intentional, and therefore potentially relevant to our interpretation of the image. Imagine if you will a photographic print hanging alongside a painting done after it which reproduces it so precisely that viewers must stare hard at the surface of each to determine which is which. In terms of what they represent, their content is exactly the same. But we don’t look at them the same way—and they aren’t saying the same thing.

What is significant in this distinction is not so much the images’ content but their grammar. To be more specific (and jargonistic), the difference is analogous to grammatical mood: it lies not in what the images are saying, but in how—and why—they are saying it. Photographs document, memorialize, and evoke particular acts of human perception; therefore they tend to address us in the declarative mood: they tell us, foremost, that they represent actual phenomena, i.e. objects that were present and/or events that were occurring in physical space at the instant the shutter was opened. Paintings work in approximately the opposite way: because we know that what they show us has been filtered through the painter’s eye and mind and brush, we also know that we have no independent access to whatever real-world phenomena (if indeed there were any) the painter set out to represent, and that the factual basis for the representation is unavailable to us. Therefore paintings speak to us in moods other than the declarative: subjunctive, imprecative, optative, inferential, mirative, speculative, hypothetical. They always provide more reliable evidence about the subjectivity of their creators than they do about the phenomena they seem to depict.

When painting and photography begin to converge—when paintings conceal their makers’ brushstrokes and decisions, and when photos become more synthetic and controlled—then things start to get interesting, grammatically speaking. In such cases the images engage actively with our expectations, trying to anticipate and to get in front of what we already know and think and feel about whatever it is they show us. In doing so, their speech becomes compromised, modulated, dynamic: the images reason and argue with us; they persuade, warn, seduce, cajole, and deceive us; they mock, joke, suggest, and wonder. Rather than allowing us to bypass issues of verisimilitude, images like these put those issues squarely in our faces, and insist that we consider whether the world they represent is the same world we inhabit. These are the kinds of images that Norman Rockwell produced. When I say that Rockwell is always rhetorical, this is what I mean.

Although this kind of visual rhetoric becomes easy to spot when we look at painting and photography in relation to each other, I think it’s important to note that it predates the birth of chemical photography (though not that of modern optics) by kind of a lot. As Dave Hickey points out in his great essay on Robert Mapplethorpe in The Invisible Dragon (“Nothing Like the Son”), Caravaggio was already working this way at the turn of the 17th Century: rather than awing and overwhelming his audience through enormous scale and startling special effects, his ecclesiastical paintings present the mysteries and the miracles they depict as tactile, intimate, and natural—not as cataclysms disrupting the texture of ordinary life, but as possibilities latent in the everyday.

“Just as Christ opens his wound to Saint Thomas,” Hickey writes,

Caravaggio (presuming to persuade us from our own doubt and lack of faith) opens the scene to us, in naturalistic detail. And we, challenged and repelled by the artist’s characterization of us as incredulous unbelievers (and guilty in the secret knowledge that, indeed, we are), must respond with honor, with trust, by believing—and not, like Thomas, our eyes. (To look is to doubt.) To free ourselves from guilt, and from Caravaggio’s presumption of our incredulity, we must transcend the gaze, see with our hearts, and acquiesce to the gorgeous authority of the image, extending our penitential love and trust to Christ, to the Word, to the painting, and, ultimately, to Caravaggio himself.

Pretty cool trick—if it’s 1602, that is, and you’re Caravaggio, better equipped than anybody else in Europe to spring that kind of image on your unsuspecting, visually innocent audience. If, on the other hand, it’s 1943 and you’re Norman Rockwell, then your circumstances are rather different: advances in photographic and print technology have made photo-oriented magazines like Life and Look and National Geographic commercially viable and increasingly popular, and American readers have grown accustomed to seeing content accompanied by photos instead of illustrations. Suddenly it seems less of a given that editors will keep sending work your way.

(Being stylistically out-of-date wasn’t Rockwell’s only reason to be nervous in ’43; the editorial page of his cash cow, the Saturday Evening Post—which printed his famous Four Freedoms series after the Office of War Information had initially passed on them—had consistently opposed both the New Deal and American involvement in World War II. Since the entire purpose of Rockwell’s Four Freedoms was to promote the sale of war bonds by illustrating principles articulated in FDR’s 1941 State of the Union, one imagines that this made for some lively meetings in the Post’s editorial offices.)

In a few fairly pointed passages in his book Secret Knowledge, David Hockney draws a connection between “lens-based” images (e.g. optically “realistic” painting, sculpture, photography, and film) and the great despots of the mid-20th Century, who he says demanded a stock of such images “to consolidate their power.” This is an important observation, but it implies that lens-based images are inherently antithetical to freedom, which I think overstates the case. Sure, images like these ARE potentially dangerous, if only because they’re politically operative—but this is just another way of saying that they’re rhetorical. A painting like Caravaggio’s The Incredulity of Saint Thomas (above) certainly DOES serve to consolidate the power of the Church that subsidized its creation, in much the same way (as Hickey demonstrates) that Mapplethorpe’s sleek and elegant porn valorizes submission of a very different kind (and to no established order). But Rockwell—who paints not at the cutting edge of image-making technology but in an avowedly outmoded style, with the evident aim of encouraging not capitulation to authority and/or uncritical jingoism, but only an expansion of positive liberty—is up to something else.

To help bring out this contrast, let’s take a quick look at a couple of Rosies:

That, obviously, is Rockwell on the bottom, and J. Howard Miller’s iconic badass on the top. Context accounts for some of the differences: Miller’s was a 1942 factory poster for Westinghouse, while Rockwell’s was a 1943 Saturday Evening Post cover. Miller meant his audience to look at his poster and see themselves; as such, his image is skimpy on particularizing detail. It’s direct, stylized, almost cartoonish; you can imagine him producing it without the use of a model, never mind a projected photograph. Its purpose is straightforward, and so is its rhetoric: the image reassures and inspires workers via appealing example, aiming to defuse any cognitive dissonance arising from the idea that assembly line work is unfeminine. (Its clarity and simplicity also make it portable, arguably more potent today, repurposed as a campy feminist signifier, than it ever was as war-effort propaganda.)

Rockwell’s Rosie is targeted at exactly the same cognitive dissonance, but in an entirely different set of brains: those of the Post’s bourgeois readers, who hadn’t yet necessarily decided how they felt about the war, never mind the sweeping cultural changes it brought about—and who certainly weren’t sending their daughters into the factories. Rockwell doesn’t set out, as Miller does, to nip in the bud anyone’s discomfort about nice young ladies wielding pneumatic hammers. In fact, this discomfort is what this image uses for fuel, what makes it work.

Unlike Miller’s maid of Westinghouse, Rockwell’s Rosie neither offers nor requires encouragement: she’s in her element, unmistakably working-class. Odds are good that she had a factory job before the war, and she damn well expects to keep punching the clock after the boys have come home. Rather than addressing social worries about women headed for the assembly lines, Rockwell draws our attention to women who have already been there, making them visible, then elevating them as contemporary icons—partly in jest, but mostly not. None of the image’s intertextual jokes—the billowing flag, the Mein Kampf footrest, the halo floating above the face-shield, the compositional allusion to Michelangelo’s Isaiah—are made at Rosie’s expense, or at anybody’s, really, except for maybe Hitler’s. Instead they serve to inch the image away from “realism” in the direction of fantasy and gentle parody, a move that creates a safe, non-confrontational rhetorical space in which the Post’s subscribers can encounter this imposing alien being. While Miller sets out to naturalize his Rosie—to insist that there’s nothing weird about ladies in factories—Rockwell acknowledges the strangeness of his image, foregrounds it, amplifies it, and then reassures his audience that it’s totally okay, that this is different but not bad, and that big girls with rivet guns are part of what makes this crazy nation of ours so freaking great.

As Richard Halpern writes in his Rockwell book,

Rockwell’s Rosie is such a compelling performance because it is such an ambiguous one. Rockwell participates in the [Office of War Information] propaganda campaign without entirely subordinating himself to it. It is not that he shrinks from his imposed task; rather, his very enthusiasm pushes him to produce something unexpected. He gives even more than he is asked, and that “more” complicates and ennobles the image. His Rosie thus sends an officially sanctioned message without being contained by it.

The addition of this complicating and ennobling “even more” is Rockwell’s signature move, something we see all over his work. It’s what gives his rhetoric its distinctive flavor, and is also, I would argue, what makes him a major American artist. The move basically works like this: Rockwell zeroes in on an instance where some set of codified social norms is scraping up against some other such set. Then he depicts the scene—in a style that suggests the alert and impersonal objectivity of a photograph—from a perspective that privileges neither set of norms. The resulting image suggests and demonstrates that these contradictory norms can tolerate each other, can peacefully and even productively coexist. Once you start noticing this signature move (something the conservatives who idolize these images seem incapable of doing) it becomes apparent in a hurry that Rockwell’s real subject is never the norms themselves, but rather the all-but-invisible liberal-democratic society in which these encounters occur, and which makes them possible in the first place.

The key thing to catch here is that Rockwell’s images deliver this message without making any discernable effort to convince, without any recourse to debate-club tactics geared solely toward scoring easy points. His images never reduce or simplify for the sake of argument; they never pump us up with myths or fascinate us with superhuman iconography. Instead they go about their work honestly and in good faith, deftly conjuring—by means of their perceptive xenophilia, their documentarian preciseness, and a profligate surplus of imaginative detail (which all together constitute the “even more” that Halpern identifies)—a vivid sense of a world distinct from but directly adjacent to the one we inhabit, a world that could be constructed here through nothing more than a collective effort of will and materials we already have on hand.

What I’m trying to say is that Rockwell’s visual rhetoric is not propagandistic, as many of his detractors claim; neither is it idealistic, as Deborah Solomon suggests in the NYT. Rather, it is very specifically fictional. Fiction (like obscenity) is one of those concepts that everybody thinks they understand—I know it when I see it!—but then has a hell of a time actually defining when push comes to shove. Fiction just means stuff that’s not true, right? Well, no, not exactly. Fiction stakes no fast claims on “truth” or “reality;” it just asks its audience to set such considerations aside and roll along with whatever it has to say, deep into wildernesses of grammatical mood. Fiction’s primary aim is not to get its audience to think (although the audience probably will think) nor to feel (ditto) but rather, in a broad sense, to imagine. If a particular fiction works on us, our experience is not necessarily one of being convinced, or emotionally moved, but rather of being transported. Successful fiction leaves us with the feeling that—although the movie ends after the last frame, the book after the last page, the painting at the edges of its canvas—the invented world that it has put into our heads somehow just keeps going. (This is no less true if the invented world is, say, contemporary Baltimore than it is if it’s the entirely fanciful Kingdom of Florin.) If, as Bismarck said, “politics is the art of the possible,” then fiction is far more politically efficacious than any overtly political discourse could ever be, since expanding the scope of what’s possible is fiction’s bread and butter.

Once we’ve identified Rockwell’s aims and methods as fictional, it becomes clear why his images look the way they do. Although Rockwell is pursuing his goals at an advanced level, his project is basically an extension of the traditional task of a certain type of commercial illustrator: one who specialized in producing naturalistic images to accompany narrative texts, very often prose fiction. (Or maybe advertising, which is a subset of fiction.) These images’ object was to provide imaginative access to the worlds these texts described—worlds in which pirates chase galleons off the Spanish Main, worlds in which shirts stay wrinkle-free without ironing—by being convincing, which typically meant depicting key episodes with near-photographic clarity and richness of incidental detail, such that readers could imagine themselves as eyewitnesses. (This is, of course, a mass-market upgrade of the same tricks that Caravaggio built his career on.)

In this sense, Rockwell can be placed in a long line of American illustrators that includes Winslow Homer, Thomas Eakins, Howard Pyle, Frederic Remington, Frank E. Schoonover, and N. C. Wyeth, all of whom labored to evoke mythic and alien settings: the open sea, the American West, feudal Britain. (Some of their near-contemporaries among European academic painters—Delacroix, Gérôme, Alma-Tadema—specialized in classical and oriental scenes executed in a similarly detailed fashion, to comparable ends. Good rule of thumb: anytime you see an image that looks like a photograph, but isn’t, you are probably looking at somebody’s fantasy of something.) Here it’s useful to contrast the working methods of these illustrators with those of another group that specialized in caricature, i.e. the stylized and exaggerated images that accompanied news and topical commentary, featuring reductions and simplifications intended to reassure readers that complex issues were within their grasp. Rockwell’s achievement, of course, involved something akin to a synthesis of these approaches: like the caricaturists, he lay claim to the “real world” as his subject—but instead of offering analysis about it, or making sweeping proclamations, he focused on capturing the quotidian experience of living in that world, and made that experience seem as intense and as outlandish as the jousts and cattle drives and battles at sea that were his colleagues’ stock-in-trade.

If Rockwell seems old-fashioned—which for a long time he has—it’s due not so much to the irrelevance of his sensibilities as it is to the irrelevance of his methods. It’s not hard to find images that work like Rockwell’s do (many a New Yorker cartoon, for instance, sings in the same bemused and affable key), but good luck finding images that look like his. If Rockwell has been out of fashion since the Sixties, then Pyle and Schoonover and N. C. Wyeth are at this point pretty much esoterica. These artists’ slide into irrelevance has closely tracked the decline of the kinds of stories they used to illustrate—by which I mean prose fiction in general, but also a particular type of prose fiction, the type that revels unselfconsciously and expansively in its own exoticism and limitless capacity for invention, a type that is disinclined to spike its wonder with any irony. I’m talking about geeky fiction. It is surely significant that about the only places you’re likely to see the work of the aforementioned illustrators emulated are the covers of sci-fi and fantasy novels; these days even romance publishers seem sheepish about their long dalliance with Fabio, more apt to go the demure flowers-embossed-on-the-cover route instead.

But let’s not be too hasty here. Intemperate lust for tales of high adventure and weird fantasy didn’t just evaporate from American life at about the time JFK was shot. Sure, geeks had it rough through most of the cool and callous Seventies, with little save Star Trek in syndication to sustain them, but they bided their time in underground exile, regrouped, and bounced back with a vengeance in about—oh, gosh, let’s see—May of 1977.

Looking back, it seems clear enough that the principal mission of George Lucas’s life—a mission at which he has basically succeeded—has been to achieve a seamless fusion of painted and photographic images. It seems difficult to overstate the degree to which the products of Lucasfilm, Ltd. (along with those of Industrial Light & Magic and Pixar, respectively its current and former subsidiaries) have altered the big-budget filmmaking process, making it not only possible but routine for directors and cinematographers to marry lens-based and purely synthesized footage into something that audiences will buy as an entirely plausible evocation of another world.

Fan lore identifies a screening of abstract experimental films that Lucas caught in the mid-1960s as his big teenage a-ha moment, and that story basically checks out: we can certainly see Stan Brakhage in Star Wars, if only manifest in the idea that film is a writable surface that can capture the images of other writable surfaces (an idea that starts to get pretty interesting, and lucrative, once you have access to a bluescreen). But by this point we should ALSO be able to recognize the perverseness of Brakhage’s painted-upon celluloid as a reverse analogue of another perverseness surely encountered by Lucas in his childhood, namely that of the commercial illustrators who adorned the pages of the adventure stories he loved—whose key working methods often involved staging elaborate photographs of models in costume, then projecting those photographs onto blank surfaces and repainting them in minute detail. Boiled down to their essences, Brakhage’s goal and the goal of these illustrators was the same: to keep ahead of audience expectations by playing a shell game with reality and artifice, accident and intention; to pass off as organic and autonomous what has actually been laboriously constructed; in short, to help us trick ourselves. It seems to me that Lucas’s gifts as technician and storyteller—though vastly amplified by his epoch-making technological vision—are roughly comparable to those of Howard Pyle or N. C. Wyeth: what he has contributed to the image-making toolbox will endure long after his films—which, by and large, are quite bad—have all been forgotten.

Lucas’s friend, collaborator, and fellow Rockwell-gatherer Stephen Spielberg, on the other hand, is by a wide margin the most significant American filmmaker of his generation. In her NYT piece, Deborah Solomon alludes to the fact that although Lucas owns many more Rockwells than Spielberg does, Spielberg owns more good ones. “He paid more,” Lucas explains. Okay, maybe. Then again, it could be that Spielberg has a clearer understanding of how Rockwell actually works—and a better sense of what (aside from their unabashed sentimentality) distinguishes his images from those of the other naturalistic commercial illustrators we discussed above.

I sort of suspect that the latter may be the case, because a lot of Rockwell’s notable traits and signature moves—which at this point have pretty much vanished from the realm of static visual art—pop up in Spielberg’s films all the time. One aspect of this influence is purely technical, and widely shared: even as early as the Thirties, plenty of filmmakers were looking to Rockwell (who was himself looking back to Pyle, Homer, La Tour, Rembrandt, Caravaggio, et al.) for ideas on how to effectively light and block and frame their shots. What Spielberg seems to have picked up better than most are the narrative (rather than purely aesthetic) functions of Rockwell’s techniques; he seems to aspire not only to compose his shots like Rockwell’s images, but also to edit them in such a way as to suggest the experience of looking at a Rockwell. Since film can’t provide the luxury of studying an image until all of its telling detail has emerged, Spielberg has learned to deftly guide our attention exactly where he wants it to be, and to do so in such a way that we feel like we got there on our own. He’ll typically accomplish this by means of efficient reaction takes—broadly acted, but carefully chosen—which is exactly how Rockwell’s narratives work. As a result of this approach, Spielberg’s most effective scenes often feel like animated Rockwells, like Rockwells sprung to life and into motion.

(It’s interesting to note—and I wish I could take credit for this observation, but I heard it a few years ago from the artist Adam Frelin—that the balance of indebtedness seems to have tipped back lately in the direction of the art world: Spielberg’s films are obvious and acknowledged points of reference for Gregory Crewdson and many other contemporary photo artists—and it’s not too tough to find evidence of his influence in other places you wouldn’t necessarily think to look, like the mid-career work of Cindy Sherman and Jeff Wall.)

Technical similarities notwithstanding, Spielberg’s principal debt to Rockwell isn’t aesthetic or narrative. It’s ideological—and, of course, it’s rhetorical. More than just about anybody else I can think of, Spielberg (at his best) shows us the world through Rockwell’s lens: he displays the same fascination with and affection for otherness that we find in Rockwell, and he too seeks to embody and encourage toward such otherness an attitude of openness, generosity, and gentle humor. Spielberg is one of the all-time great portrayers of friendship—not of longstanding friendships in the bromantical or Sex-&-the-City veins, but rather of unexpected, often fleeting comradeship between entirely dissimilar individuals. The cinematic gold standard here is probably the geopolitically fraught relationship in Casablanca between Rick Blaine and Capt. Louis Renault, but Spielberg has made some admirable additions to the field: think of Roy Scheider’s transplanted big-city cop and Richard Dreyfuss’s dorky marine biologist in Jaws, or Liam’s Neeson’s Nazi industrialist and Ben Kingsley’s Jewish accountant in Schindler’s List, or even the brief exchange between Tom Hanks and Matt Damon in Saving Private Ryan. Think most of all, however, of Close Encounters of the Third Kind and E.T., Spielberg’s two most personal films, as jaw-dropping a pair of fantasies as you’re ever likely to see about escaping the prison of the alienated self through sympathetic contact with a radically alien other.

Spielberg’s achievements, like Rockwell’s, are crowned with a couple of asterisks—probably best regarded as caveats, not dealbreakers, but still worthy of note. No matter how pure its intentions, a work of art that’s motivated by love of the unfamiliar and the exotic will not tend to encourage understanding of whatever cultures or individual it depicts. (Understanding, in fact, spoils all the fun.) This limitation creates certain dangers that artists ought to guard against, and that they probably won’t: see, for example, the gee-whiz, aw-shucks, devil-may-care racism of Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom. (Temple was, of course, a collaborative venture between Spielberg and Lucas; I’m not going to try to argue that Spielberg was blameless in this mess—but still, one of these two guys went on a year later to make The Color Purple, while the other one gave the world Jar Jar Binks. That’s all I’m saying.) Rockwell’s track record is actually somewhat better than Spielberg’s on both gender and race—particularly after 1963, when Rockwell finally left the Saturday Evening Post (which had a longstanding prohibition of images of African-Americans, unless they were depicted as servants) and began working for Look. (His great civil rights images, such as The Problem We All Live With—apt to shock anybody who just knows Rockwell from, like, that Thanksgiving turkey picture—all date from this period.) Whether Rockwell and Spielberg can legitimately claim the authority to depict whatever and whomever they please is a valid question, and one that ought to be periodically revisited—although I predict that we’re consistently going to find that, yes, they can indeed. Even so, we’d do well to keep in mind that their rhetorical posture—like any rhetorical posture—obliges them to be silent on certain subjects, even as it frees them to speak eloquently on others.